5 Proofreading enzymes

Sometimes the type of polymerase you use during library construction will influence the type of damage pattern you will receive.

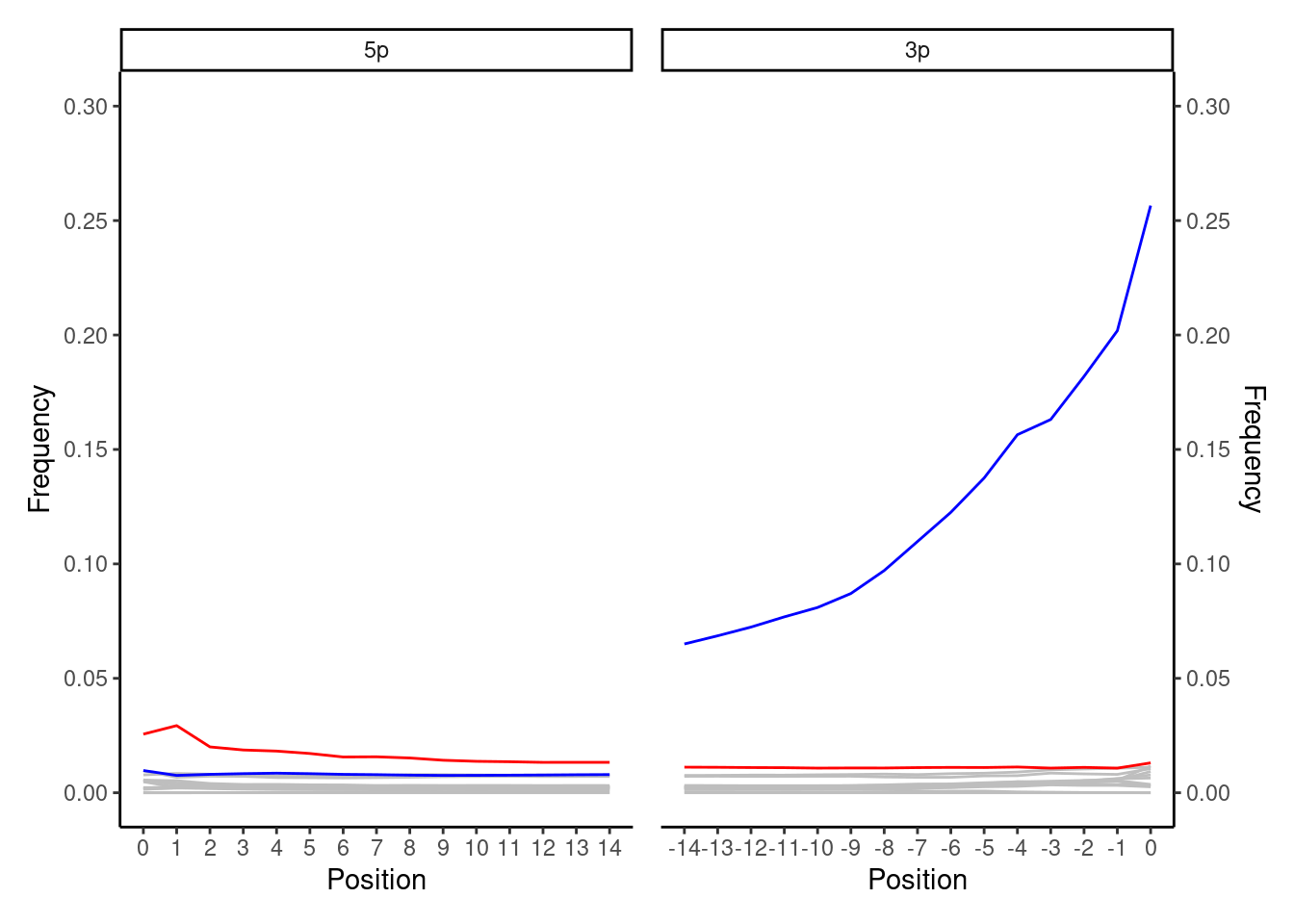

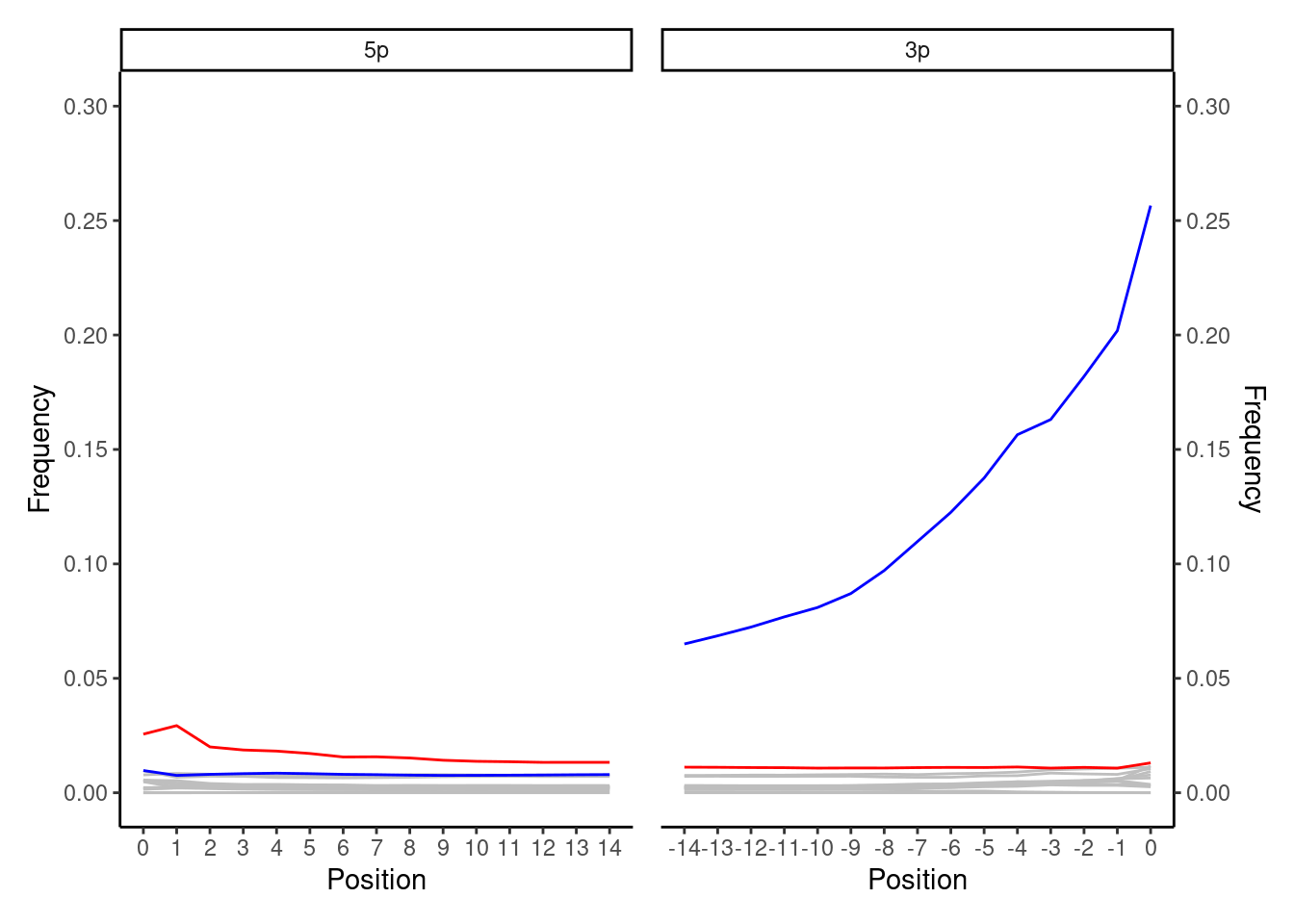

In the example above, Cai et al. (2022) found a funny smiley plot, where while the 3’ G to A patterns look like a classic non-UDG (i.e. non-USER treated, thus retaining damage) plot, the frequency of C to T on the 5’ end was extremely reduced. This is because of the choice of polymerase used during library amplification was not conductive to the nature of ancient DNA.

In this paper, the Q5® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase was as the polymerase for the intial amplification after adapter ligation. This polymerase has no tolerance for uracils.

During amplification, when it encounters a uracil, it cannot proceed with extending the newly forming complement strand. As the original strand with the uracil will not be copied. Thus the C-to-T deamination at the 5’ termini of the reads will be absent in the plot.

In contrast, the original complementary DNA strand (that contains the adenine opposite uracil), which is filled-in by T4 DNA polymerase during the blunt-ending step of the double-stranded library preparation (Briggs et al. 2007), will still be amplified by the Q5 polymerase. This means the G-to-A misincorporation pattern is retained in 3’ termini of the reads, even if the damage signal were lost on the first strand.

While having a low error rate is great for modern genomics, this can be less optimal for preserving ancient DNA damage for profiling later on. Furthermore, you may have lost a fraction of true ancient DNA reads (those that have uracils in both strands).

In the case of this particular enzyme, it may not too much of a problem to prove authenticity visually as you retain the damage signal on the 3’. However this may be problematic for downstream aDNA validation tools that may have an expected ‘model’ of ancient DNA damage.

The choice of enzyme only matters during the first amplification after adapter ligation. At subsequent amplifications, the (misincorporated) thymines have already been integrated into the template molecules, so it doesn’t matter which enzyme you use.